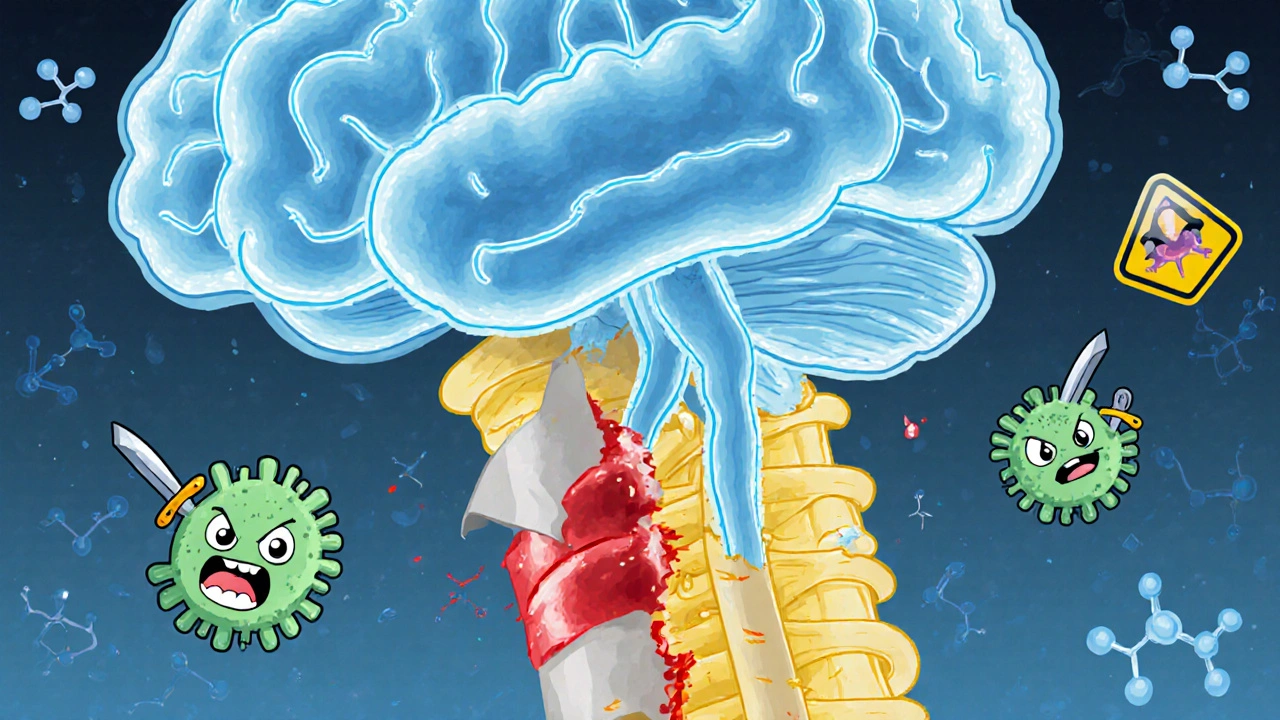

Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological condition-it’s an internal betrayal. Your own immune system, trained to protect you, turns against the very nerves that let you move, see, and think. It strips away the protective coating around nerve fibers, like pulling insulation off a wire. The result? Signals from your brain get scrambled, delayed, or lost entirely. This isn’t theory. It’s happening in real time inside the brain and spinal cord of nearly 3 million people worldwide.

What Happens When the Immune System Goes Rogue

The central nervous system-your brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves-is normally shielded by the blood-brain barrier. This barrier keeps out rogue cells and toxins. But in multiple sclerosis, something breaks. Immune cells, especially CD4+ T cells and B cells, slip through. Once inside, they mistake myelin-the fatty sheath wrapped around nerve fibers-for a foreign invader.

Myelin isn’t just padding. It’s the insulation that lets electrical signals zip along nerves at lightning speed. When immune cells attack it, the myelin breaks down in patches called lesions. These lesions show up on MRI scans as bright spots. But what’s worse than the damage itself is what happens after. The body should repair myelin. Oligodendrocytes, the cells that make myelin, are ready and waiting. But the inflammation doesn’t let them. The environment stays toxic. Scar tissue forms instead. That’s what creates the "sclerosis" in multiple sclerosis-hard, fibrous scars.

There are four known patterns of this damage, each with different immune fingerprints. Some lesions are dominated by T cells. Others show antibodies clinging to myelin. Some involve outright death of myelin-making cells. And in the worst cases, no repair happens at all. The immune system doesn’t just attack-it prevents healing.

Who’s at Risk and Why

MS doesn’t strike randomly. Genetics play a role, but they’re not the whole story. Someone with a parent who has MS has a 2-5% chance of developing it-higher than the general population, but still low. That means environment triggers the switch.

One of the biggest culprits? Epstein-Barr virus. Nearly everyone with MS has been infected with EBV, the virus that causes mononucleosis. Studies show people who’ve had EBV are 32 times more likely to develop MS than those who haven’t. It’s not that EBV causes MS directly. It’s that the virus changes how the immune system remembers threats. Later, immune cells get confused and start targeting myelin.

Vitamin D deficiency is another major player. People living far from the equator-Canada, Scandinavia, northern U.S.-have higher MS rates. Sunlight helps your body make vitamin D. Low levels mean your immune system doesn’t get the signal to calm down. Smoking? That increases your risk of progression by 80%. It damages the blood-brain barrier and fuels inflammation.

Women are two to three times more likely to get MS than men. The reasons aren’t fully clear, but hormones, immune system differences, and even how women’s bodies respond to infections may all contribute.

The Symptoms: When Your Nerves Go Silent

There’s no single MS symptom. What you feel depends on where the immune system attacks.

Optic neuritis is one of the most common first signs. Vision blurs, colors fade, or pain shoots behind the eye. That’s because the optic nerve-connecting your eye to your brain-has lost its myelin. It can happen over hours or days. For many, vision returns, but the damage lingers.

Numbness, tingling, or a feeling like your limbs are "asleep" affects more than half of people with MS. That’s not a pinched nerve. That’s a signal getting blocked in the spinal cord. Walking becomes harder. Balance fades. Fatigue hits like a brick wall. Eight out of ten people with MS describe it as overwhelming, unrelenting, and unrelated to how much they’ve done.

Then there’s Lhermitte’s sign. Bend your neck forward, and you feel a sudden electric shock running down your spine. It’s startling. It’s not dangerous. But it’s a direct result of demyelination in the cervical spine. Your brain misreads the signal as pain.

Bladder control issues, muscle spasms, dizziness, even trouble speaking or swallowing-these aren’t random. They’re direct outcomes of nerve damage in specific brain regions. The more lesions, the more symptoms. But even one lesion in the wrong spot can change your life.

Two Types of MS: Relapse and Decline

Most people-about 85%-start with relapsing-remitting MS. They get flare-ups: new symptoms that last days or weeks, then fade. These are active immune attacks. MRI scans show new lesions forming. Blood tests show inflammation rising.

Between attacks, many feel almost normal. That’s the remission. But here’s the catch: even when symptoms disappear, damage is still happening. Tiny amounts of nerve fiber loss add up. That’s why, over time, even people with relapsing MS start to decline.

The other 15% have primary progressive MS. No flares. No remissions. Just a slow, steady worsening. From day one, their nervous system is under constant, low-grade attack. This form is harder to treat. The immune cells aren’t as visible in blood tests. The damage is more about neurodegeneration than inflammation.

Without treatment, half of relapsing MS patients need help walking within 15 to 20 years. With modern therapies, that number drops to about 30%. That’s the power of early intervention.

How Treatments Stop the Attack

There’s no cure yet. But we have tools that stop the immune system from tearing up your nerves.

Ocrelizumab targets B cells-the immune cells that produce antibodies and pump out inflammatory chemicals. In clinical trials, it cut relapses by 46% in relapsing MS and slowed disability progression by 24% in primary progressive MS. It’s given as an IV infusion every six months.

Natalizumab blocks immune cells from crossing the blood-brain barrier. It’s incredibly effective-reducing relapses by 68%. But it comes with a serious risk: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare brain infection. The risk goes up after two years of use. Doctors test for the JC virus before starting this drug.

Other drugs like fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate, and cladribine work by trapping immune cells in lymph nodes or wiping out overactive ones. Each has different side effects, dosing schedules, and risk profiles. The goal isn’t just to reduce flares-it’s to prevent long-term disability.

And now, researchers are looking beyond suppression. One drug, clemastine fumarate, showed in early trials that it could help rebuild myelin. Patients saw a 35% improvement in nerve signal speed. It’s not a cure, but it’s the first real sign that repair might be possible.

What’s Next: The Future of MS Treatment

The field is shifting from broad immune suppression to precision targeting. Scientists now know that dendritic cells in the brain are handing myelin fragments to T cells, keeping the attack alive. Blocking those cells could stop the cycle without wiping out the whole immune system.

Neutrophil extracellular traps-NETs-are another new target. These sticky webs, released by immune cells, break down the blood-brain barrier and activate microglia. In 78% of acute MS relapses, NET biomarkers spike. Drugs that dissolve NETs are already in early testing.

Blood tests for neurofilament light chain (sNfL) are becoming routine. When levels rise above 15 pg/mL, it means active nerve damage is happening-even if you feel fine. This lets doctors adjust treatment before symptoms get worse.

The International Progressive MS Alliance has poured $65 million into research since 2014. Projects are underway in 14 countries. The goal? To turn progressive MS from a death sentence into a manageable condition.

Living With MS: It’s Not Just About Drugs

Medicines help. But lifestyle matters too. Exercise improves strength, balance, and mood. Physical therapy keeps you moving. A diet rich in omega-3s and low in processed foods reduces inflammation. Quitting smoking isn’t optional-it’s essential.

Mental health support is just as important. Depression and anxiety are common. The stress of living with an unpredictable disease takes a toll. Support groups, like those on Reddit’s r/MS, help people feel less alone. Stories like "my vision went blurry overnight" or "I lost feeling in my foot and thought it was a stroke" are shared, not just to vent, but to prepare others.

MS isn’t a death sentence. It’s a lifelong condition. But with early diagnosis, the right treatment, and smart lifestyle choices, most people live full, active lives. The immune system may have turned against them. But science is turning back.

Elaina Cronin

The precision of this exposition is unparalleled. The delineation between immune-mediated demyelination and neurodegenerative attrition is not merely accurate-it is ethically imperative to communicate with such clarity. To reduce MS to a ‘neurological condition’ without contextualizing the autoimmune betrayal is to commit a disservice to the afflicted. This is not speculation; it is histopathology rendered in human language. I commend the author for refusing euphemism.

Willie Doherty

EBV correlation is statistically significant but causation remains unproven. The 32x multiplier is misleading without adjusting for seroprevalence-over 90% of adults are EBV+. Correlation ≠ causation, and conflating the two undermines scientific rigor. Also, vitamin D’s role is confounded by latitude-based lifestyle variables. This article reads like advocacy, not analysis.

Darragh McNulty

This hit me right in the soul 🥺 I’ve seen my sister go from hiking the Wicklow Way to needing a cane in 3 years. But seeing the science behind it-how the body turns on itself-made me feel less alone. Ocrelizumab gave her back her mornings. And clemastine? That’s the light at the end of the tunnel 💪🧠 Let’s keep pushing for repair, not just suppression.

Cooper Long

MS is not an American disease. It is a global neurological phenomenon with distinct epidemiological patterns. The focus on U.S. treatment protocols obscures the reality that access to ocrelizumab or natalizumab is nonexistent for the majority of patients in low-income nations. Science advances, but equity lags. The article is medically sound but sociologically blind.

Sheldon Bazinga

lol so basically your immune system is just bad at its job? and now we got some rich folks gettin fancy iv drips while the rest of us pay 500 bucks for a pill that makes us feel like zombies. ebv? yeah right. its just the vaccines. i read it on a forum. also vitamin d is just sunshine bro. why you think canada got so many cases? they dont know how to tan.

Pravin Manani

From a neuroimmunology standpoint, the delineation of four lesion patterns (Type I-IV) is critical. Type II, with antibody and complement deposition, suggests humoral dominance-hence B-cell targeting efficacy. But the persistent microglial activation and failure of remyelination implicates a failure in oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) differentiation, not merely inflammation. The NETs hypothesis is promising-neutrophil-derived histones and MPO directly degrade myelin and disrupt BBB integrity. sNfL as a biomarker is now validated in the MAGNIMS guidelines. We’re entering an era of preemptive neuroprotection.

Daisy L

Okay, but WHY is it women?!! Like, is it our hormones? Our immune systems are just… extra dramatic?? 😤 I mean, I get it-estrogen modulates Th17 responses, but why does nature do this to us?? And why do we still have to fight just to get insurance to cover ocrelizumab?! This isn’t science-it’s a gendered betrayal. And don’t even get me started on how doctors still dismiss fatigue as ‘just stress’!!

Corra Hathaway

Y’all are overthinking this. I’ve had MS for 12 years. I do yoga, eat turmeric, and dance in my kitchen when the pain flares. I don’t need a 10-page breakdown of T-cells to know I’m still alive, still laughing, still here. You think science will cure it? Nah. But resilience? That’s the real treatment. Keep moving. Keep loving. Keep being weird. 🌈💪

Shawn Sakura

Shawn here-diagnosed 7 years ago. Just wanted to say: this article got me through a dark week. I cried reading the part about oligodendrocytes trying to repair but being choked by inflammation. I didn’t know that’s what was happening inside me. I started physical therapy last month. My foot tingles less. I’m not ‘cured’… but I’m fighting back. Thank you for writing this with such care. 💙