NMS Symptom Checker

NMS Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps assess whether a patient may be experiencing Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS). NMS is a rare but potentially fatal reaction to antipsychotic medications. Early recognition is critical for survival.

Based on the article, NMS is characterized by four key symptoms: muscle rigidity, hyperthermia, altered mental status, and autonomic instability. The tool evaluates which of these symptoms are present and calculates the likelihood of NMS.

Symptom Assessment

Select all symptoms present in the patient. The more symptoms present, the higher the risk of NMS.

Assessment Results

Select symptoms to see results...

Next Steps:

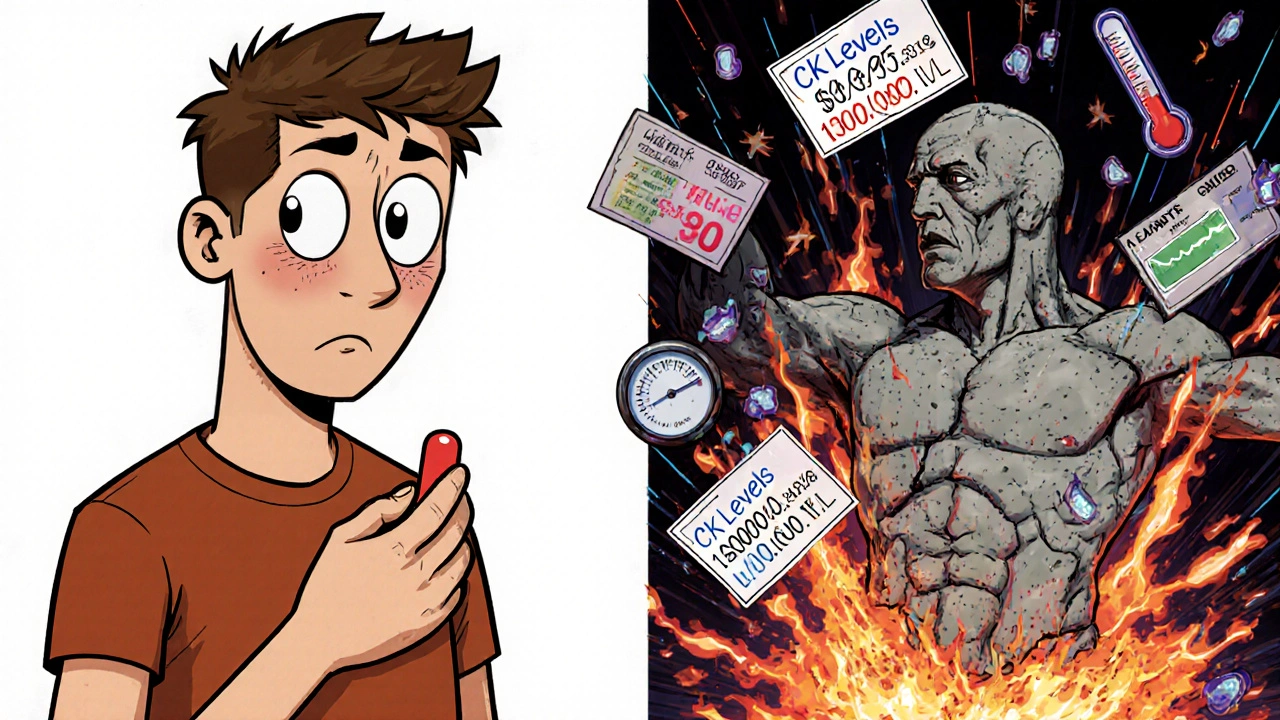

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) isn’t something most people have heard of - until it happens. It’s rare, but when it does, it can turn a routine medication change into a life-or-death emergency. Picture this: someone on antipsychotics for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder suddenly becomes rigid, feverish, and confused. Their heart races, their muscles lock up like concrete, and their body temperature spikes past 104°F. At first, doctors might think it’s a psychotic episode worsening - or an infection. But it’s neither. It’s NMS, and every hour counts.

What Exactly Is Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome?

NMS is a severe, sometimes fatal reaction to medications that block dopamine in the brain. These include older antipsychotics like haloperidol and a first-generation antipsychotic that carries a higher risk of NMS due to strong D2 receptor blockade, and even some anti-nausea drugs like metoclopramide and a dopamine antagonist used for nausea, responsible for about 15% of NMS cases. It’s not an allergy - it’s a neurological cascade triggered by sudden dopamine withdrawal in key brain areas.

The core problem? Dopamine isn’t just about mood. It’s critical for movement, temperature control, and autonomic functions like heart rate and sweating. When antipsychotics block dopamine receptors in the hypothalamus and basal ganglia, the body loses its ability to regulate these systems. The result is the classic four-part symptom combo: muscle rigidity, high fever, mental changes, and unstable vital signs.

The Four Hallmarks of NMS

Doctors don’t rely on one test to diagnose NMS. They look for a pattern - and timing matters. Symptoms usually show up within 1 to 2 weeks of starting or increasing a neuroleptic drug, though they can appear as fast as 48 hours or as late as months later.

- Muscle rigidity - not just stiff muscles, but "lead pipe" rigidity. When you move someone’s arm, it feels like bending a metal pipe - no give, no resistance variation. This isn’t spasms or tremors. It’s constant, full-body stiffness.

- Hyperthermia - body temperature above 38°C (100.4°F), often climbing to 40°C (104°F) or higher. Fever doesn’t respond to normal meds like acetaminophen because it’s not caused by infection.

- Altered mental status - confusion, agitation, delirium, mutism, or even coma. Patients may stare blankly, not respond to questions, or become violently agitated.

- Autonomic instability - rapid heartbeat (over 90 bpm), blood pressure swings, fast breathing, and excessive sweating. Some patients go from high to low BP in minutes.

These symptoms don’t all show up at once. Typically, mental changes come first, then rigidity, then fever, then autonomic chaos. Missing the early signs is common - and dangerous.

Lab Tests That Confirm the Diagnosis

There’s no single blood test for NMS, but labs help rule out other causes and show how bad it is. The most telling marker is creatine kinase (CK), a muscle enzyme. In NMS, CK levels often spike above 1,000 IU/L - sometimes over 100,000 IU/L. That means muscles are breaking down, a condition called rhabdomyolysis.

Other common lab findings include:

- White blood cell count over 12,000/µL (leukocytosis)

- Low serum iron (under 60 µg/dL)

- Metabolic acidosis (bicarbonate under 22 mEq/L)

- High potassium (over 5.0 mEq/L)

- Elevated liver enzymes

These aren’t just numbers - they signal real danger. High CK means myoglobin is flooding the kidneys, which can cause acute kidney failure in up to 30% of cases. That’s why fluids and urine output monitoring are non-negotiable in treatment.

How NMS Is Different From Serotonin Syndrome and Malignant Hyperthermia

Doctors often confuse NMS with two other life-threatening conditions. But the differences are critical.

| Feature | Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome | Serotonin Syndrome | Malignant Hyperthermia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | 1-14 days after starting/changing drug | Hours after taking serotonergic drug | Minutes after anesthesia exposure |

| Muscle sign | Lead-pipe rigidity | Clonus, hyperreflexia, myoclonus | Masseter spasm, generalized rigidity |

| Temperature | Often >40°C | Usually <40°C | Rapid spike, often >41°C |

| Key trigger | Antipsychotics, metoclopramide | SSRIs, SNRIs, tramadol, MDMA | Volatile anesthetics, succinylcholine |

| GI symptoms | Mild or absent | Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting common | Usually absent |

| Response to dantrolene | Yes, often helpful | Less effective | First-line treatment |

Clonus - that involuntary muscle twitching - is a red flag for serotonin syndrome. If a patient has it, NMS is unlikely. Malignant hyperthermia hits fast, during surgery, and is tied to anesthesia, not psychiatric meds. Mixing these up leads to wrong treatments - and worse outcomes.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

NMS doesn’t strike randomly. Certain factors make it more likely:

- Using first-generation antipsychotics and older drugs like haloperidol with high D2 affinity - risk is 10 to 100 times higher than with newer drugs.

- Rapid dose increases - jumping haloperidol by more than 5 mg/day is a known trigger.

- Injectable antipsychotics - depot injections or IV use spike risk.

- Combining antipsychotics with lithium or dehydration.

- Being male and under 40 - men are twice as likely to develop NMS.

- Having bipolar disorder - higher incidence than schizophrenia.

Even more surprising: 60% of cases happen when someone first starts the drug. Another 30% occur during a dose increase. Only 10% happen after months of stable treatment. That’s why the first few weeks are the most dangerous.

What Happens If It’s Not Treated?

Untreated NMS kills. Between 10% and 20% of patients die from complications like kidney failure, heart rhythm problems, or blood clots. Even with treatment, 5% still don’t make it - but that’s down from 20% in the 1980s. Why? Better awareness and faster action.

But survival isn’t the whole story. Survivors often face months of recovery. One patient on a mental health forum described taking eight weeks to walk again after muscle damage. Others report permanent weakness, fatigue, or anxiety about ever taking antipsychotics again. That’s a huge problem - because stopping meds can mean a return of psychosis.

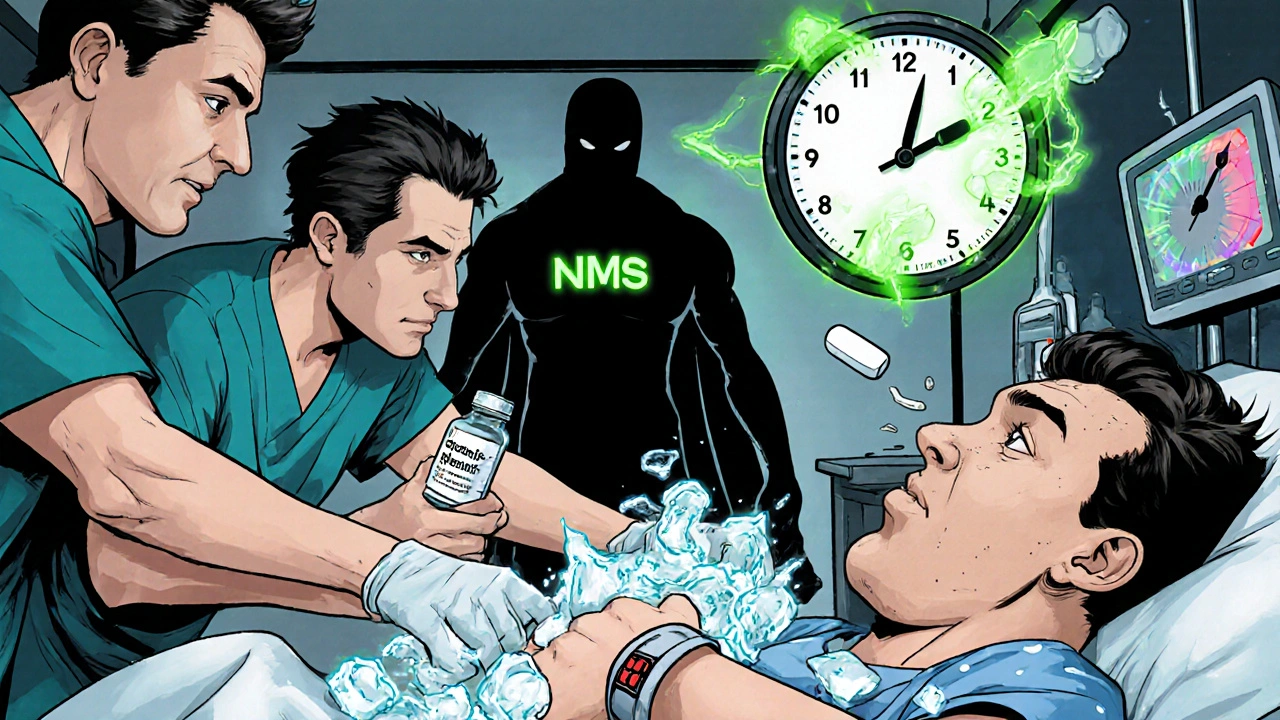

How NMS Is Treated - Step by Step

There’s no magic pill. Treatment is aggressive, fast, and happens in the ICU. Here’s what works:

- Stop the drug immediately. No exceptions. All dopamine-blocking meds - even anti-nausea drugs - must be discontinued.

- Cool the body. Ice packs, cooling blankets, and IV fluids to bring temperature down. Never use aspirin - it can worsen bleeding risks.

- Hydrate aggressively. At least 1-2 liters of IV fluids upfront, then 100-150 mL/hour to protect the kidneys. Urine output must stay above 30 mL/hour.

- Use dantrolene. This muscle relaxant (1-2.5 mg/kg IV) helps reduce rigidity and heat production. It’s not a cure, but it buys time.

- Try bromocriptine or amantadine. These boost dopamine in the brain. Bromocriptine (2.5-10 mg every 8 hours) can speed recovery, especially if given early.

- Monitor CK, kidneys, and electrolytes. CK peaks at 72-96 hours. If it keeps rising, kidney damage is likely. Some patients need dialysis.

It’s not glamorous, but it works. In a 2023 Cleveland Clinic study, patients treated within 24 hours had a 95% survival rate. Those treated after 48 hours? Survival dropped to 70%.

What Comes After Recovery?

Once symptoms fade - usually in 7-10 days - the real challenge begins: restarting psychiatric treatment. Many patients refuse to take antipsychotics again. And rightly so. The trauma is real.

But going without meds can mean relapse. The solution? A cautious return, using second-generation antipsychotics and atypical agents like quetiapine, olanzapine, or clozapine with lower D2 binding. These have a 100-fold lower risk of NMS. Start low, go slow. Never rush. Some doctors avoid antipsychotics entirely and use mood stabilizers or newer agents like lumateperone.

Patients who survive NMS need long-term follow-up. Muscle weakness can linger. Anxiety about meds is common. And yes - they should wear a medical alert bracelet.

The Bottom Line

NMS is rare, but it’s not mythical. It happens. And it’s often missed. Emergency rooms get it wrong 12% of the time. Primary care doctors? Even more. If someone on antipsychotics suddenly becomes rigid, hot, and confused - don’t assume it’s psychosis. Don’t wait for labs. Don’t give more sedatives. Act.

Stop the drug. Get them to the hospital. Start cooling. Start fluids. Call for ICU help. That’s it. No delay. No guesswork. Because in NMS, time isn’t just money - it’s life.

Can NMS happen with antidepressants?

No, not directly. NMS is caused by dopamine blockers, not serotonin boosters. But some antidepressants like trazodone or bupropion can rarely contribute if combined with antipsychotics. The main culprits are antipsychotics and anti-nausea drugs like metoclopramide.

How long does it take to recover from NMS?

Most patients start improving within 2-3 days of treatment and fully recover in 7-10 days. But muscle damage can take weeks or months to heal. Some survivors report weakness or fatigue for over a month. Full recovery is possible, but it’s not instant.

Can you get NMS from stopping Parkinson’s meds?

Yes. Sudden withdrawal of levodopa or other dopamine-boosting drugs in Parkinson’s patients can trigger a similar syndrome called "Parkinsonism-Hyperpyrexia Syndrome." It’s essentially NMS caused by dopamine withdrawal, not blockade. Symptoms appear within 24-72 hours of stopping meds.

Is NMS more common in older adults?

Actually, no. NMS is more common in younger adults, especially men under 40. Older patients are more likely to get serotonin syndrome or delirium from meds. But age doesn’t protect you - anyone on dopamine-blocking drugs is at risk.

Are newer antipsychotics safer?

Yes. Second-generation antipsychotics like olanzapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole have much lower NMS risk - about 0.01% to 0.02% compared to 0.5%-2% for older drugs like haloperidol. They’re not risk-free, but they’re dramatically safer.

Can NMS come back after recovery?

Yes, but it’s rare - under 5% of cases. Recurrence usually happens if the same drug is restarted too quickly or at too high a dose. If antipsychotics must be restarted, use a low-potency atypical agent, start at 10-25% of the previous dose, and increase very slowly over weeks.

For anyone managing psychiatric care - whether a doctor, nurse, caregiver, or patient - remember this: NMS is rare, but it’s real. It doesn’t care if you’ve been doing this for years. It doesn’t care if the patient "seems stable." If the signs are there, act now. Because in NMS, hesitation kills.

Brad Samuels

It’s wild how something so rare can be so devastating. I’ve seen a cousin go through this after a haloperidol shot-doctors thought it was a psychotic break for hours. By the time they realized, he was in ICU. The rigidity was like he’d turned to stone. It’s not just medical-it’s emotional trauma for the whole family. We still don’t talk about it much.

Mary Follero

As a nurse in psych, I’ve seen this twice. The first time, I caught it because the patient’s CK was sky-high and they weren’t sweating-classic NMS red flag. Most nurses miss it because they’re trained to see psychosis, not neurology. But once you know the four signs-rigidity, fever, mental change, autonomic chaos-you can’t unsee it. Please, if you’re on antipsychotics and feel stiff or weirdly hot, don’t wait. Go to the ER. And tell them you’re on meds. Don’t assume they’ll ask.

Will Phillips

Big Pharma doesn't want you to know this but they've been covering up NMS for decades. They push these drugs like candy then blame the patient when they melt down. Why do you think they changed the names of the drugs? To hide the connection. And don't get me started on the FDA-they're bought off. I know a guy who got NMS after metoclopramide and now he's on a feeding tube. They didn't even warn him. It's all about profit. Wake up people. This isn't medicine. It's chemical slavery.

Arun Mohan

Actually, the entire paradigm of neuroleptic use is fundamentally flawed. You're treating phenomenological disturbances with pharmacological blunt instruments. The dopamine hypothesis is a 1950s reductionist fantasy. NMS isn't a side effect-it's the inevitable consequence of violating homeostatic integrity. We need epistemic humility here. The body isn't a machine. It's a dynamic field of emergent processes. You can't just jam a receptor antagonist in and expect equilibrium. The fact that we still use haloperidol is a testament to our collective intellectual laziness.

Tyrone Luton

It's interesting how society treats mental illness like a glitch in the code. We medicate people into compliance, then act shocked when their bodies rebel. NMS isn't an accident-it's a rebellion. The body says, 'No more.' And we call it a syndrome. We don't call it what it is: a scream from the nervous system. We'd rather blame the drug than the system. The real tragedy isn't the fever or the rigidity. It's that we still think this is normal.

Jeff Moeller

Man I remember when I was on risperidone and my arm locked up for 10 mins after a dose. Thought it was just stress. Turned out it was early NMS signs. Doc said it was nothing. Now I only take clozapine. Low risk. Low fuss. And yeah I know some people say it's dangerous too but the NMS risk is like 1 in 10000. Way better than haloperidol. Just say no to old school antipsychotics.

Hannah Machiorlete

So you're telling me that people who take meds for schizophrenia are basically walking time bombs and we just pretend its fine because they're 'stable'? That's not care thats negligence. And dont even get me started on how they get discharged before they're even stable. People die because no one wants to admit the system is broken. I know someone who lost her brother to this and they gave him a new script two days later. Like what.

Bette Rivas

One critical point often overlooked: NMS recovery doesn't end when the fever drops. Many survivors experience prolonged myopathy, with creatine kinase levels remaining elevated for weeks, and some develop chronic fatigue syndrome-like symptoms. Additionally, the psychological impact is profound-patients frequently develop medication phobia, leading to nonadherence and relapse. A multidisciplinary approach involving psychiatry, neurology, physical therapy, and counseling is essential. Many hospitals still treat this as a purely medical emergency, neglecting the long-term rehabilitation needs. The 7-10 day recovery window is misleading; true functional recovery often takes 6 to 12 weeks, and in some cases, up to 6 months.

prasad gali

From a pharmacodynamic standpoint, the D2 receptor occupancy threshold for NMS is approximately 80-90%. First-generation antipsychotics achieve this rapidly due to high affinity and slow dissociation kinetics. Second-generation agents, particularly clozapine and quetiapine, exhibit lower occupancy due to rapid dissociation and 5-HT2A antagonism, which modulates dopaminergic tone. This explains the 100-fold reduction in incidence. The key is not avoidance but kinetic optimization. Also, metoclopramide’s NMS potential is underrecognized because it’s classified as a GI agent, not a neuroleptic-this is a regulatory blind spot.

Paige Basford

Oh my gosh I had no idea NMS could happen from anti-nausea meds! I gave my dad metoclopramide after his chemo and he got super stiff and feverish. We thought it was the chemo side effects. I feel so guilty. But you know what? My aunt had it too and she’s totally fine now-she’s back to gardening and everything. I just wish someone had told us earlier. You’re right, we need to be more aware. I’m going to tell everyone I know. And maybe we should make like a little card to keep in your wallet if you’re on these meds?

Donald Sanchez

bro i had NMS after my first haloperidol shot and now i wear a medical alert bracelet and i have a tattoo that says 'NO NEUROLEPTICS' on my forearm 😎 the docs thought i was just being dramatic but i was like nah this shit almost killed me. now i only take olanzapine and i'm chill as hell. also if you're reading this and you're on antipsychotics please stop scrolling and go ask your doc about CK levels. seriously. your life could depend on it 💪🔥