Primary vs. Secondary Osteoarthritis Classifier

Use this tool to help identify whether your osteoarthritis is likely primary or secondary based on key characteristics. This is for educational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice.

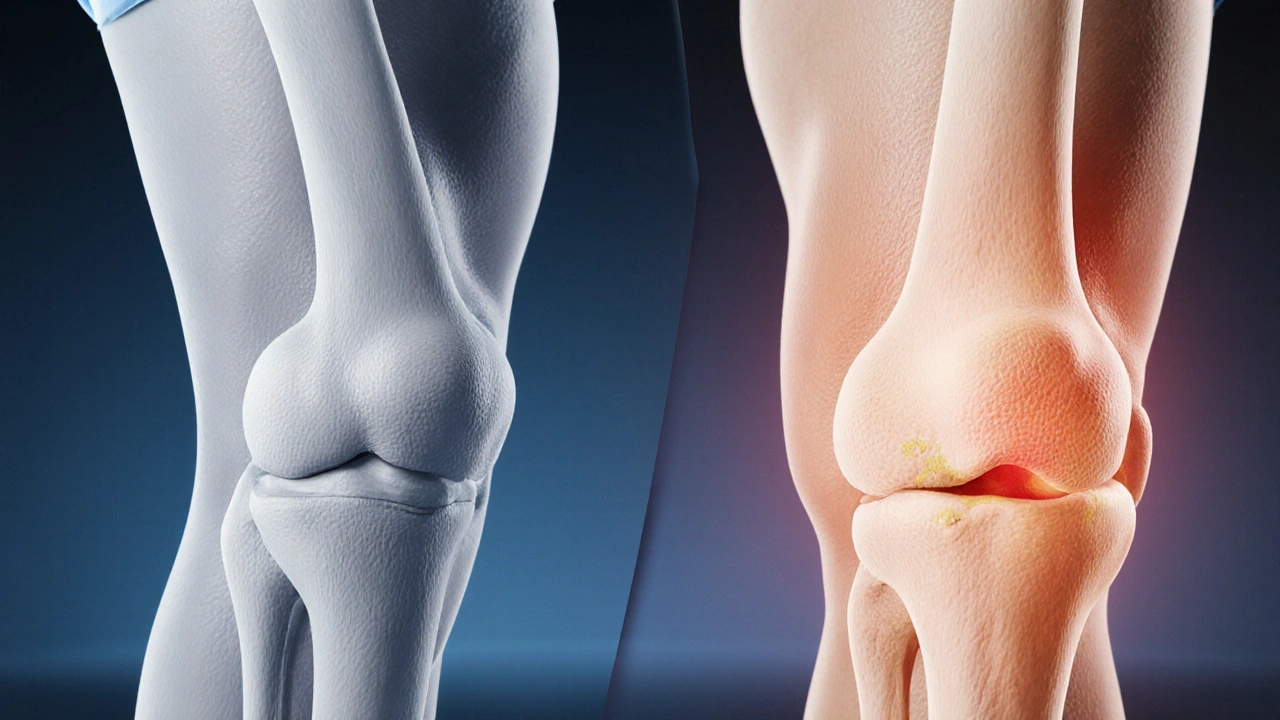

When joint pain starts creeping in and daily activities feel harder, many people wonder what’s really going on inside their knees, hips, or hands. The answer often points to osteoarthritis, a condition that comes in two main flavors: primary and secondary. Knowing which type you’re dealing with can shape the whole approach to management, from lifestyle tweaks to medical interventions.

Quick Takeaways

- Primary osteoarthritis arises from age‑related wear and tear without a clear underlying disease.

- Secondary osteoarthritis develops because of another joint problem such as injury, inflammation, or metabolic disorder.

- Both types share cartilage loss and pain, but their risk‑factor profiles differ.

- Accurate diagnosis hinges on a mix of patient history, physical exam, and radiographic imaging.

- Treatment strategies overlap but are tailored: primary focuses on slowing degeneration, secondary adds disease‑specific interventions.

What is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a chronic joint disorder characterized by the breakdown of articular cartilage and changes to the surrounding bone. It leads to pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. Worldwide, more than 300 million adults live with the condition, making it the most common form of arthritis.

Primary Osteoarthritis: The Classic Wear‑and‑Tear

Primary osteoarthritis typically appears in middle‑aged to older adults and is linked to the natural aging process. The cartilage’s extracellular matrix gradually loses water and proteoglycans, making it less resilient. Over time, micro‑fractures develop, leading to joint space narrowing visible on X‑rays.

Key risk factors include:

- Age - incidence rises sharply after 50.

- Genetic predisposition - family studies show a 40% heritability factor.

- Obesity - each extra kilogram adds roughly 0.5kg of load on knee cartilage.

- Joint shape - certain knee alignments (varus/valgus) accelerate wear.

Secondary Osteoarthritis: When Another Problem Takes Over

Secondary osteoarthritis emerges as a consequence of a distinct joint insult. The trigger can be a traumatic injury, an inflammatory arthritis, metabolic disease, or even congenital malformation.

Common precursors are:

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture - uncontrolled joint instability leads to uneven cartilage loading.

- Rheumatoid arthritis - chronic synovial inflammation damages cartilage despite a different primary pathology.

- Hemochromatosis - iron overload can deposit in joint tissues, hastening degeneration.

- Developmental dysplasia of the hip - abnormal joint congruence creates early wear.

Because the underlying cause is identifiable, treatment often merges standard osteoarthritis measures with disease‑specific therapy (e.g., disease‑modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid‑related secondary OA).

How Doctors Tell Them Apart

The diagnostic process blends patient history, physical exam, and imaging. While both types look similar on plain radiographs - joint space loss, osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis - clues emerge from the narrative.

Radiographic imaging plays a central role. An X‑ray can show Kellgren‑Lawrence grades that quantify severity. MRI adds detail about cartilage thickness and bone marrow lesions, helping to spot secondary causes such as meniscal tears.

Key differentiators:

- Onset age - primary usually after 50; secondary can appear much earlier if injury occurred.

- Pattern of joint involvement - post‑traumatic knees often affect the same compartment that was injured.

- Associated symptoms - systemic inflammation (fever, morning stiffness) points toward secondary origins.

Comparing Primary and Secondary Osteoarthritis

| Aspect | Primary Osteoarthritis | Secondary Osteoarthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Typical onset | After age 50 | Any age, often after injury or disease |

| Main cause | Age‑related cartilage wear | Identifiable joint insult (trauma, inflammation, metabolic) |

| Common joints | Knees, hips, hands | Knees (post‑trauma), ankles (post‑fracture), hips (developmental) |

| Progression speed | Gradual, over years | Can be rapid if underlying cause persists |

| Treatment focus | Weight management, exercise, pain control | Address root cause + standard OA care |

Management Strategies for Both Types

While the underlying trigger differs, the symptom relief toolbox overlaps.

Treatment options include:

- Lifestyle modification - weight loss can cut knee joint load by up to 4kg per kilogram lost; low‑impact aerobic activity (swimming, cycling) improves joint nutrition.

- Physical therapy - targeted strengthening of quadriceps and hip abductors stabilizes joints.

- Pharmacologic relief - NSAIDs for pain, topical capsaicin for mild cases, and intra‑articular corticosteroids for flare‑ups.

- Viscosupplementation - hyaluronic acid injections can improve lubrication, especially in primary knee OA.

- Surgery - total joint replacement is considered when pain limits daily living despite conservative care.

For secondary osteoarthritis, you’ll also see disease‑specific interventions. Example: a patient with hemochromatosis may undergo regular phlebotomy to reduce iron load, indirectly slowing joint damage.

Practical Tips to Differentiate at Home

While a doctor’s evaluation is essential, you can gather useful information before the appointment:

- Note the age when symptoms first appeared.

- Recall any past joint injury, surgery, or diagnosed condition (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis).

- Observe if pain worsens after specific activities - climbing stairs often aggravates primary knee OA, while twisting injuries may trigger secondary symptoms.

- Track systemic signs like morning stiffness lasting over an hour - that leans toward an inflammatory cause.

Bring this list to your clinician; it speeds up the diagnostic conversation.

Future Directions: Personalized Medicine in Osteoarthritis

Researchers are exploring biomarkers (e.g., serum CTX‑II, urinary C‑telopeptide) that could predict whether a patient’s OA is primary or secondary before imaging. Genetic panels are also gaining traction; certain COL2A1 mutations raise primary OA risk, while HFE gene variants flag secondary OA due to iron overload.

In the next few years, clinicians may combine these biomarkers with AI‑driven imaging analysis to offer truly personalized treatment plans - for instance, recommending early joint‑preserving surgery for secondary OA patients with high‑risk genetic profiles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I develop primary osteoarthritis if I’m under 40?

It’s uncommon but possible, especially if you have a strong family history, joint malalignment, or a metabolic condition that stresses cartilage earlier than typical age‑related wear.

Is secondary osteoarthritis reversible?

The cartilage loss itself isn’t reversible, but treating the underlying cause (e.g., repairing a ligament tear, controlling inflammation) can halt further damage and improve symptoms.

Do I need surgery for secondary osteoarthritis?

Surgery is considered when conservative measures fail and pain limits daily life. In secondary OA, surgeons also address the original problem, such as correcting alignment or fixing a chronic instability, before joint replacement.

How accurate are X‑rays in distinguishing primary from secondary OA?

X‑rays show structural changes but can’t always reveal the cause. MRI or CT scans, combined with a detailed history, are needed to spot secondary triggers like meniscal pathology or inflammatory synovitis.

What lifestyle changes benefit both types of osteoarthritis?

Maintaining a healthy weight, staying active with low‑impact exercises, strengthening surrounding muscles, and avoiding prolonged joint immobilization help slow cartilage loss and reduce pain in both primary and secondary cases.

Understanding whether you’re facing primary or secondary osteoarthritis is more than an academic exercise-it directs the right care plan and can improve quality of life. By paying attention to the age of onset, past injuries, and any accompanying systemic signs, you empower your healthcare provider to tailor a treatment that tackles both symptoms and root causes.

Sam Matache

Wow, this whole primary vs secondary OA thing is like a soap opera of joints. First you’ve got the boring old wear‑and‑tear, then BAM! an injury crashes the party. It’s maddening how doctors love to toss these labels around while we’re stuck limping around. I swear, if my knee could talk it’d file a grievance.

Hardy D6000

Honestly, the article oversimplifies the biomechanical reality. Primary OA isn’t just "age‑related wear", it’s a cascade of molecular events that the author glosses over. Similarly, labeling every post‑traumatic case as secondary ignores the nuanced overlap in pathophysiology.

Amelia Liani

I totally get the frustration of trying to figure out which OA you have. When I first felt knee pain at 48, I thought it was just “getting old”. Then a car accident a year later made everything worse, and that’s when the secondary label clicked for me. It really does change how you approach treatment – from simple weight loss to maybe surgery to fix the ligament.

shikha chandel

One must recognize that the taxonomy presented is reductive, designed for lay consumption rather than scientific rigor.

Zach Westfall

Okay this is super helpful but i wish there were more pics i mean pictures of knees and hips would make it easier to understand the differences

Kelly Thomas

First off, kudos to the author for pulling together such a thorough overview of primary and secondary osteoarthritis – it’s a topic that can easily become a tangled mess if not presented clearly.

What really stands out to me is the emphasis on the age of onset as a diagnostic clue; many patients (including myself) dismiss early joint pain as a temporary nuisance, only to discover years later that a subtle injury set the stage for secondary OA.

Understanding that primary OA is essentially the cumulative wear‑and‑tear of cartilage over decades helps frame lifestyle interventions – weight management, low‑impact cardio, and targeted strength training become the cornerstone of slowing disease progression.

Conversely, identifying secondary OA opens the door to treating the root cause, whether that’s a repaired ligament, disease‑modifying therapy for rheumatoid arthritis, or even phlebotomy for hemochromatosis.

The table comparing the two types is a gold‑standard quick reference; I’ve bookmarked it for future consultations with my physio.

Another point worth highlighting is the role of genetics; a family history can predispose you to primary OA even before the age of 50, underscoring the importance of early screening in at‑risk individuals.

In terms of imaging, while plain X‑rays are useful for grading joint space loss, MRI can reveal early cartilage lesions and meniscal tears that point toward a secondary etiology – a nuance that many primary‑care providers miss.

From a therapeutic perspective, the article correctly points out that both types share a toolbox of NSAIDs, hyaluronic injections, and physical therapy, but the nuance lies in adding disease‑specific strategies for secondary OA.

For instance, someone with post‑traumatic OA might benefit from arthroscopic debridement to address loose bodies, while a patient with inflammatory secondary OA needs DMARDs alongside joint care.

The lifestyle tips are practical: a 5‑kg weight loss can reduce knee load by roughly 20 kg, and regular swimming sessions keep the joint lubricated without imposing shear stress.

Don’t overlook the psychological impact either; chronic pain can lead to depression, and addressing mental health is essential for adherence to rehab programs.

Future directions mentioned, like biomarkers and AI‑driven imaging, are exciting. Imagine a blood test that tells you whether your OA is primary or secondary before any X‑ray – that could revolutionize early intervention.

In my own experience, early detection meant I could adjust my training regimen and avoid high‑impact sports that would have accelerated damage.

Overall, this piece does an excellent job bridging the gap between academic detail and patient‑friendly guidance, and I would recommend it to anyone navigating the confusing landscape of joint health.

Mary Ellen Grace

Sounds useful.

Carl Watts

When we contemplate the dichotomy of primary versus secondary osteoarthritis, we are, in effect, engaging in a micro‑cosmic reflection of the larger philosophical debate between determinism and contingency. The wear‑and‑tear of cartilage may be seen as an inevitable march of entropy, yet the sudden infliction of trauma or the insidious whisper of systemic inflammation reminds us that the universe is replete with abrupt ruptures in the tapestry of causality. Thus, the clinical practitioner becomes a modern‑day sophic, tasked with deciphering whether the joint’s story is one of slow, inevitable decline or of disruptive intervention. In either case, the pursuit of understanding remains a noble endeavor, anchored in both empirical observation and contemplative insight.

Brandon Leach

Oh great, another deep‑thought about knees. Sure, philosophy is fun until your knee decides to quit mid‑sentence.

Alison Poteracke

This article does a solid job breaking things down. If you’re dealing with OA, start with a simple plan: keep moving, watch your weight, and talk to your doctor about any injuries you’ve had.

Marianne Wilson

While the advice is well‑intentioned, it suffers from a lack of precision. Statements like “keep moving” are overly vague; readers need specific activity recommendations, frequency, and progression metrics to avoid misinterpretation.

Patricia Bokern

Did you know the government hides a cure for OA because they want to keep us buying pain meds? All that “research” is a front.

Meredith Blazevich

I love how this piece balances the hard facts with a dash of human story. It reminds me of my own journey – the first twinge in my hips at 45 felt harmless, but a slipped disc a few years later turned everything upside down, pushing me into the secondary camp. Knowing the difference helped me focus on rehab for the disc while still paying attention to my overall joint health. The practical tips, like tracking the age of onset and noting any systemic symptoms, are exactly what I wish my doctor had asked me at my first appointment. It’s not just about the numbers on an X‑ray; it’s about the narrative that each patient lives through.

Nicola Gilmour

Great read! If you’re dealing with any kind of joint pain, remember you’re not alone – tiny daily steps and a supportive community can make a huge difference.